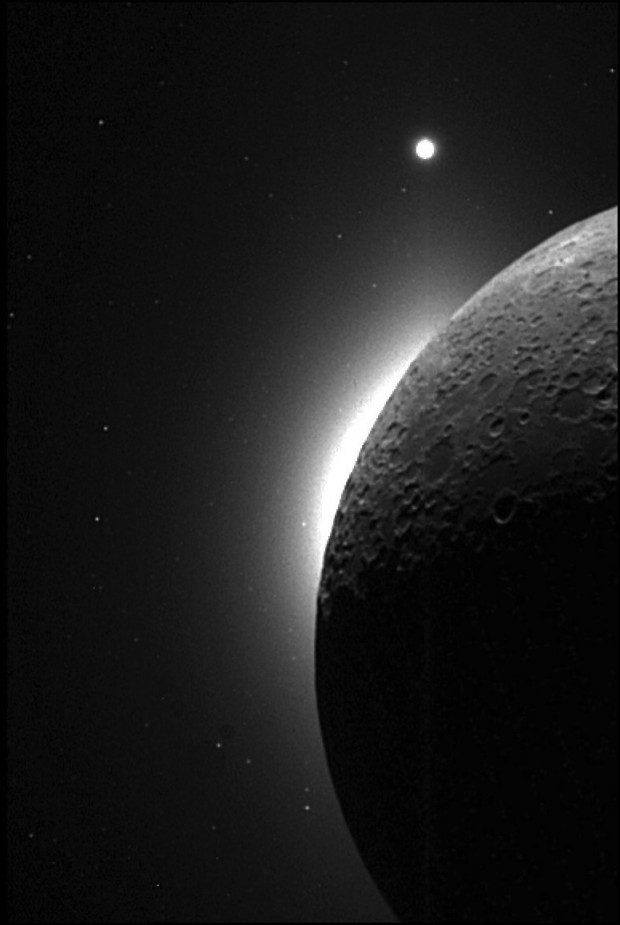

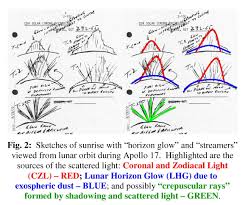

Just before sunrise, Apollo 17 astronaut Eugene Cernan spotted a strange glow circling the horizon of the moon. He was expected to see some light from the sun, rays from the outer corona just as in sunrises on earth, but the shape and behavior of the glow—a crescent-shaped illumination with distinct beams—puzzled scientists.

Even since that sighting in 1972, and earlier camera observations in 1966 by the Surveyor landers, the so-called Lunar Horizon Glow has mystified scientists and space buffs alike. Some spacecraft spot it, other times it isn’t apparent. The moon has just a smidgen of an atmosphere, particles aren’t likely to collide, much less scatter enough light to brighten the horizon.

To resolve the puzzle—and glean lessons that might be applicable to other moons—NASA launched the Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer

(LADEE, pronounced laddie) last year. LADEE crashed into the moon, as planned, on April 17.

Although most of the data remains to be analyzed, LADEE didn’t find anything capable of explaining the quirky glow, according to Rick Elphic, LADEE project scientist. “So far the measurements of dust we do see aren’t dense enough to produce the glow,” Elphic said. “It’s still something of a mystery.”

NASA’s lunar missions in the 1960s and 70s spotted a heavy form of argon, emitted from the moon’s, and helium, in the moon’s tenuous atmosphere. And in the 1980s, ground-based telescopes discovered sodium and potassium. “We didn’t know what else was there, but we suspected a lot of other things,” Elphic said.

LADEE carried three scientific instruments: an ultraviolet and visible light spectrometer, a mass spectrometer to detect variations in the atmosphere’s composition, and equipment that measured the quantity of lunar dust. They observed neon, magnesium, titanium and possibly other elements as well, Elphic said.

And although LADEE didn’t reveal the origin of the lunar dust, it did chronicle the behavior of the moon’s atmosphere and the powerful effect of the significant temperature variation, he said. Like a desert, the lunar atmosphere heats up quickly when it is bathed in sunlight, rising to more than 100 degrees Celsius.

Once out of range of the sun, the temperature plummets within minutes, Elphic said. Most of the elements observed in the atmosphere fall to the surface during the lunar night, then change into gaseous form and lift off during the toasty day, he said.

Quoting another NASA scientist, Elphic said the elephants “hop around the surface like bunnies.” Elphic said he expects other exciting results to emerge from the data, which is being analyzed by scientists at NASA’s Ames Research Center and at the University of Colorado, Boulder. ![]()

Comments are closed.