Being a science writer is kind of like being an aunt. When you’re an aunt, you get to go on the strolls through the park, bounce the baby on your knee, and play peek-a-boo. But when that smile turns to a frown, the water works begin, and things get stinky, it’s time to hand off that putrid bundle of joy to mom and dad.

When you’re a science writer, you get to tag along and peer over shoulders as scientists do their thing. Sometimes you even get to participate – provided it’s fun and there’s a low chance of you screwing up and/or breaking something. Then when the math comes in you can let the experts take over.

That’s just what I got to do a couple weeks ago at Elkhorn Slough in Moss Landing. I met Ana Garcia-Garcia at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco last December. She told me about her research using ultrasound to “X-ray” the slough’s many layers of sediment.

“That’s really cool,” I said.

“Do you want to come with us next time?” she asked.

Recognizing the opportunity to go play in the mud, I enthusiastically agreed. Often times these exchanges are forgotten until much later, but Ana didn’t forget about me. A few months later an email popped into my inbox inviting me to come along with her and her physical Piggyslots geology class to the slough to do some coring. I agreed so she asked me how I take my coffee.

When I arrived, she greeted me with a big hug and handed me a cup of warm black coffee – just what I needed to get going on the overcast Saturday morning. As the class gathered she explained to them how the day’s events would go. There were a lot of activities on the docket but first and foremost was that everyone was required to get in the water and get their hands dirty. The first science-y thing that we did was sampling the top layer of sediment on the slough’s floor using the ponar sampler, or The Claw, as I liked to call it.

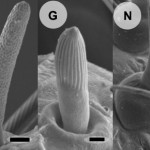

The ponar sampler is a neat little contraption that is way scarier than it looks. It’s basically a spring-loaded machine. You pull the pin out until it’s about to pop out on its own so that when the open claw hits the bottom of the slough the shock jettisons the pin and the claw closes. With a lot of force. Enough to take off a finger, probably. Thankfully it’s not as easy to get The Claw into that just-about-to-snap state as it may seem. After three or four tries I finally got it to grab a sample. We even caught some sea lettuce with tunicates on it. Tunicates, by the way, are the invertebrates most closely related to humans.

The sediment that we picked up from The Claw was soft, grey, and fine. It’s the easiest kind of sediment to move around and it makes sense that it’s on top.

The water in the slough has been calm for some time and lacks the energy to move heavy things like sand and rock. But 18,000 years ago, when the glaciers were melting, the slough had tons of energy. Ana hoped she and her students would be able to core all the way down to the sandy layer. They did, and with that core came layers upon layers of different colored mud. There was some really dark, black mud that smelled nasty and sulfurous. That smell comes from the breakdown of organic matter. It’s evidence of when the slough supported an even richer array of life than it does now.

For me, the day ended shortly after a little boat ride around the middle section of the slough near Kirby Park. In a motor boat, we watched onlinegambling2014 data stream in as an attached “fish” sent out sound signals to the bottom of the slough. As they bounced back, we could see all the different layers of the slough, including pockets of gas that might soon escape into the water.

Hopefully I’ll get another invitation from Ana to go back soon.

Comments are closed.