Perhaps the greatest gift for the environment this holiday season would be a change in how we recycle paper. Photo courtesy of SXC.

Doe-eyed kids will rise from their comfy beds on Christmas, eager to rush downstairs and unwrap the presents under the tree, all the while, unwittingly taking a huge dump on the environment.

U.S. household waste is highest between Thanksgiving and New Years, rising by 25 percent—or an extra one million tons during the holiday season. Much of this refuse is paper—cards, gift-wrapping, and packaging—and, even though recycling rates are at their highest in American history, the bulk of what a family tosses into the plastic bin at the end of their driveway may not benefit the world in the way they expect—if at all.

The paper hierarchy is this. Virgin white paper, made directly from trees, is the monarch and carries the most value. It’s pure and perfect for notebooks, novels, and office printers. Cardboard is the dregs and a terminus that is reached after about six rounds of recycling, while gift-wrap, tissue paper, and newspaper populate the middle class.

But once white paper is recycled into a lesser product—known as downcycling—it can never return to an upper rung.

Yet the bulk of American recycled paper either winds up in a landfill—30 percent—or is shipped overseas—40 percent. Meaning only one of every three sheets of recycled paper will be recovered to manufacture new paper.

Most recycled fiber lands in China where it is mainly downcycled it into boxes for their consumer exports or newsprint.

Plus according to Daniel Press, an environmental scientist at the University of California Santa Cruz, oceanic shipping of recycled paper comes at tremendous carbon cost.

“In 2010, just the recovered fiber that we sent to China used enough energy to produce over a million tons of carbon. Just to ship, not to make,” said Press, whose upcoming book will feature a chapter on the misgivings of paper recycling.

Press described recycled fiber as valuable “raw material” that’s being given away.

Meanwhile, Americans remain addicted to virgin paper. According to the Environmental Paper Network, “if United States offices reduced virgin fiber copy paper use by 10% from 2009 levels, it would save 22.8 million trees, reduce greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to taking 481,000 cars off the road, and keep over 60,000 trucks full of solid waste out of landfills and incinerators.”

A Single Stream of Controversy

How did the U.S. reach a point where it remains the leading importer and one of the top-10 consumers of virgin paper, while also reaching a peak paper recycling output in 2012?

For the answer, head back to the end of the driveway. It’s the single blue bin. Tossing everything – glass and plastic– into one receptacle with paper introduces impurities to recovered fiber.

Imagine a teenage boy “slam-dunking” a glass bottle into the driveway canister. Those broken shards adulterate the fiber and clog the equipment that paper mills use to remake white paper. Just one percent contamination could cost the average paper mill up to $1 million annually; so many factories avoid using paper from single-stream recycling.

Things were not always this ways. California spawned the single-stream era in the late 1980s by requiring all of its cities to divert 25 percent on landfill waste into recycling.

This ultimately sparked a nationwide movement to switch to consolidated recycling.

Yet these directives didn’t specify where recycled paper should go, merely that it shouldn’t end up in landfills.

As more states adopted single-stream recycling, other nations spotted a valuable commodity piling on American shores and decided to capitalize, according to Dr. Press.

China profited the most, mainly due to the America’s growing reliance on imported goods from East Asia over the last 20 years. Legions of Chinese container ships arrived and emptied on U.S. shores, begging to be filled before returning to China.

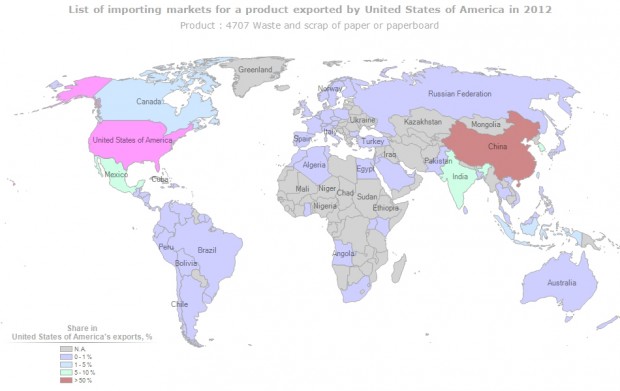

Oceanic shipping companies like 9 Dragons have made a fortune off recycled fiber and other salvaged materials. In 2012, the U.S. shipped 14 million tons of water paper—valued at $2.2 billion—to China. By comparison, India ranked number second on our paper export recipient list at 1.4 million tons—a ten-fold difference.

Some in China have moved against their country becoming the world’s dumping ground. Yet even if the legislation passes (and survives the rebuke of Chinese manufacturers), America’s lack of an outlet for its recycled paper will remain.

Return of the King?

Once upon a time, U.S. paper mills led the global market, but the industry has witnessed a steady decline. The rise of the electronics era, along with greater competition from overseas, were the main contributors, with hundreds of mills closing over the last five decades.

“Around the year 2000, there was a big consolidation within the whole paper industry,” said Susan Kinsella, executive director of Conservatree, a non-profit paper consulting firm. “Older and less efficient mills were closed. With non-recycled paper mills, they moved production into bigger and more efficient mills. With recycled mills, they just closed.”

Kinsella and Conservatree have led efforts to preserve North America’s paper recycling infrastructure. More deinking plants are needed to remove toner or pen stains from used paper. Materials recovery facilities, which separate paper from other recyclables, are also crucial to the retrieval process.

And broader use of recycled fiber could offer a solution to the paper industry’s woes.

“That’s one of the argument we’ve been making for several years. The U.S. is the motherland for recovered fiber globally,” Kinsella said. “We should be using it for our industries and not just shipping it away to other places.”

Comments are closed.