An artist’s concept of the New Horizons space probe and its item of interest, Pluto.

As the Curiosity rover safely studies rocks on the surface of Mars, a NASA mission on route to Pluto may find itself on a treacherously rocky path. NASA announced last month that the $650 million New Horizons space probe’s planned trajectory during its July 2015 flyby could turn into a collision course with unknown moons and debris circling the dwarf planet—an unfortunate end to the mission’s three-billion-mile cosmic road trip. Today the spacecraft passed the halfway point between Uranus and Neptune, our solar system’s two outermost planets.

Since New Horizons was launched in 2006, a lot has changed: Barack Obama became president and won a second term, the global economy collapsed, a South Korean pop star got us all dancing like we’re horseback riding and Pluto got demoted from a full-fledged planet to a “dwarf planet.” But the change that has NASA scientists worrying is all the new “stuff” they’ve found circling Pluto—including two previously unknown moons, bringing Pluto’s known moon count up to five.

When even a small pebble can cripple the spacecraft as it zooms through empty space at 30,000 mph, entire new moons are a big deal. Each moon is thought to be a giant icy snowball similar to Pluto and other objects past the orbit of Neptune. These moons act as “debris generators,” populating the Pluto system with shards from collisions between the moons and other objects in the area, says Alan Stern, principal investigator of the New Horizons mission.

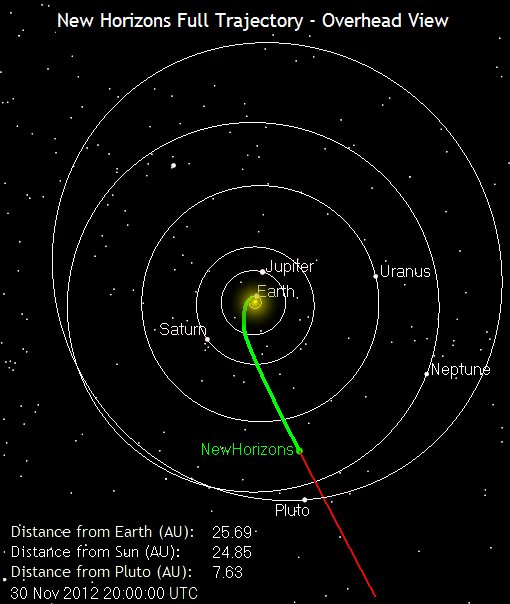

The New Horizons space probe’s position on its journey to Pluto, as of this blog post’s publication.

The team is using every tool it can get its hands on – from computer simulations to the Hubble Space Telescope – to search for dangerous debris in the Pluto system to try and pick a clear path for New Horizons. The team says it’s a tough process—limited knowledge about Pluto is, after all, why the probe was launched in the first place. The probe plans on taking photographs of Pluto, measuring its magnetic field and learning information about how the dwarf planet formed.

If New Horizon’s path seems too perilous, the team plans to set the probe on a “bail-out” trajectory farther away from Pluto. At that distance the probe will still be able to fulfill its main objectives of taking measurements and pictures of the dwarf planet, but the data collected by its assortment of sensors and cameras won’t be as ideal. If New Horizons survives its journey to Pluto, it may be sent to scout out other objects in the area.

As the probe grows closer to its journey’s end, the probe’s equipment will join the search for potential perils. But even with the extra pair of eyes, it could be a close call. The team could be flying blind until just 10 days before the probe reaches Pluto, turning the probe’s fate into a “cliff-hanger” according to Stern.

With proposed probes that could travel even further from Earth – even to other stars – the lessons learned from New Horizons’ perilous predicament will be invaluable for future missions aimed at doing science in the unknown reaches of Space. Pluto, after all, is “only” 3 billion miles away compared to the 25,000 billion miles to the closest star.

Comments are closed.