It took me a long time to learn that I have a touch of road rage. The first time my husband watched me come slightly unhinged in gridlock, he only had one thing to say: “If you’re complaining, you’re part of the problem.”

Now that I’m spending a year as a California road warrior, it’s a mantra that slaps me with perspective whenever traffic slows to a crawl.

It’s also something that I’ve been thinking about since I fell for the United Nations’ marketing ploy surrounding today’s demographic holiday.

World population is somewhere around 7 billion: “If you’re complaining, you’re part of the problem.”

When I’m the sole person in a five-passenger car, I’m definitely part of the problem. It doesn’t take long for me to redirect my road rage inward.

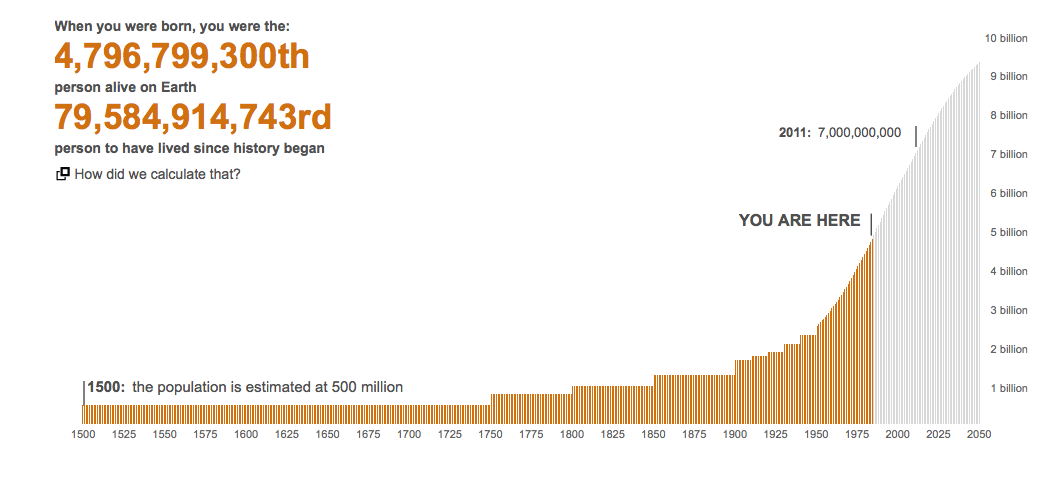

My Halloween costume is the 4,796,799,300th billion person on Earth. Go to http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-15391515 to get an estimate of your number. (Credit: BBC)

The rectangle of environmental damage

Last week, I interviewed biologist Paul Ehrlich as part of my intern duties at the Stanford News Service. Ehrlich, the author of the controversial 1968 book, The Population Bomb, described a simple way to think about the entangled issues of population growth and consumption:

How do you respond to the statement that we should focus on overconsumption, not population growth?

Ehrlich: Most of humanity’s environmental problems trace to too much total consumption, but that consumption is a product of population size and per-capita consumption. Population and consumption are no more separable in producing environmental damage than the length and width of a rectangle can be separated in producing its area – both are equally important.

The next time I find myself trapped in an argument about which one matters more, I’m going to invoke geometry.

Both population and per-capita consumption are equally important, but our contribution to population is decided for us when we’re born, and we all need food, water and shelter. But I also seem to think that I need an iPhone, a Subaru, coffee and a hot shower. Need, maybe not, but that’s what I’m choosing.

Thank you, California

In addition to all of my consumption, I just became one more body in the most populous U.S. state. Thank you California, for your fresh agricultural products and tap water, I’m enjoying your resources.

In The Population Bomb Ehrlich warned of threats to food security, the availability of and access to enough food to live a productive life free from hunger or starvation. Many of his most dire and specific predictions have not come to pass, but we’ve been innovating ways to increase food production since the book was published; yet people generally agree that the current level of hunger in the world is still unacceptable.

The Dos Amigos Pump Plant, part of the California State Water Project, 10 miles south of Los Banos on I-5. Water is pumped up 114 feet so it can flow downhill to the next station. (Photo by Sarah Jane Keller)

California is an example of how we’ve engineered more food out of the land during the past century. It also supplies the U.S. with half of its fruits, vegetables, and nuts, making it an important part of the food system in our neck of the globe.

I recently stopped along I-5 to take in some of California’s extensive plumbing that makes it all possible. The roadside attraction was the Dos Amigos Pumping Plant, part of the California State Water Project (SWP). The pump lifts water in the California Aqueduct 114 feet, so it can flow by gravity 164 miles to the next pumping plant.

The SWP delivers water to two-thirds of the state’s population, with 70 percent going to urban users and 30 percent going to agriculture, according to the California Department of Food and Agriculture. Coincidentally, many initial phases of the project were completed in the years surrounding publication of The Population Bomb.

Having read Cadillac Desert, Marc Reisner’s 1986 opus on Western U.S. water development and sustainability (or lack thereof), seeing the California Aqueduct was like spotting a celebrity. Nothing drives home how we bend natural resources to our will like watching water flow languidly through a concrete conduit, on a journey hundreds of miles through an arid landscape.

I imagined how the water in the California Aqueduct started in the Sierra Nevada, much of it as snow, and how some of it would eventually reach Southern California. To make the journey, it is pumped nearly 2000 feet over the Tehachapi Mountains that divide the San Joaquin Valley and the Mojave Desert.

California’s water system has been described as a Rube Goldberg apparatus, which is not a cliché in this case. Before he became a cartoonist, Goldberg was a sewer engineer in San Francisco.

Water in the California Aqueduct flowing south. According to Aquafornia, “70 percent of California’s runoff occurs north of Sacramento, 75 percent of California’s urban and agricultural demands are to the south.” (Photo by Sarah Jane Keller)

A paper, “Reclaiming freshwater sustainability in the Cadillac Desert”, published last year, found that “Reisner’s incisive journalism led him to the same conclusions as those rendered by copious data, modern scientific tools, and the application of a more genuine scientific method.”

Sustainability, according to the authors is defined as allocation of streamflow “to people farms and ecosystems.” They discuss issues that I have not mentioned here such as salination and impacts on biodiversity and fisheries. They mention, but do not analyze, climate change pressures on freshwater.

What would Reisner say about water in a world with 7 billion people? Sadly, we’ll never know because he was lost to cancer over a decade ago, at age 51. But an interview with Reisner, from 2000, in the now defunct magazine, California Wild, will let me give him the last word:

CW: The state’s population is projected to grow another 30 percent by 2020. If there’s enough water to fill California with people from border to border, is population growth a big problem for California?

MR: For California and the world. People ask me “What is the greatest environmental problem?” Some people think it’s water, and I say, “No. It’s population growth, by far.” It eclipses the next five most significant environmental problems combined, and in California it’s not much different.

This ending doesn’t make thinking about our roles on a planet of 7 billion any easier, but I’ll be considering how I contribute to the area of our resource sustainability rectangle, globally and in California.

If you are wondering about the source of your California tap water check out: http://www.water-ed.org/watersources/default.asp

I have a hard time imagining you with road rage!