Zooommbieeees…

Hordes of people—numbed by the Great Recession, perhaps—have once again staggered toward fresh zombie fare. But unlike other zombie fever outbreaks, splatters from the pop-culture feast are landing in the far corners of science—and they’re leaving quite the mark.

From left to right, zombified Dustin Adams, Julia Kelly, and Stephanie Lukin invade UCSC’s science hill.

Since George Romero’s 1968, genre-defining film, Night of the Living Dead, zombie zeal has lurched in and out of popularity. Some link their recurring resurrections to the economy—zombie apocalypse as blue-collar strife?—others to their flexibility.

I side more with the latter.

A few years ago, a friend and I hosted a seven-week long zombie movie series, presenting a doubleheader each week. We started with Romero’s Living Dead series then ventured to the work of successors, including Sam Raimi and Dan O’Bannon, and humorous homage, such as Slither and Shaun of the Dead.

Our audience was mostly our science comrades from biology, ecology, spatial epidemiology, and sociology, and there was something for everyone.

The zombie skeleton supports a wide variety of meaty topics—as the plumpness of the genre demonstrates—allowing writers and directors to dissect complex social issues and our fear of unknowns. But in the latest zombie outbreak, scientists are the ones biting. In fact, they’ve clamped on and welcomed shuffling zombies into narrow allies of science, including zombie parasitology, apocalypse preparation, disease ecology and zombie infection modeling, and zombified anesthesiology.

Then there’s Dr. Bradley Voytek, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of California at San Francisco, and the leading zombie brain expert with the Zombie Research Society.

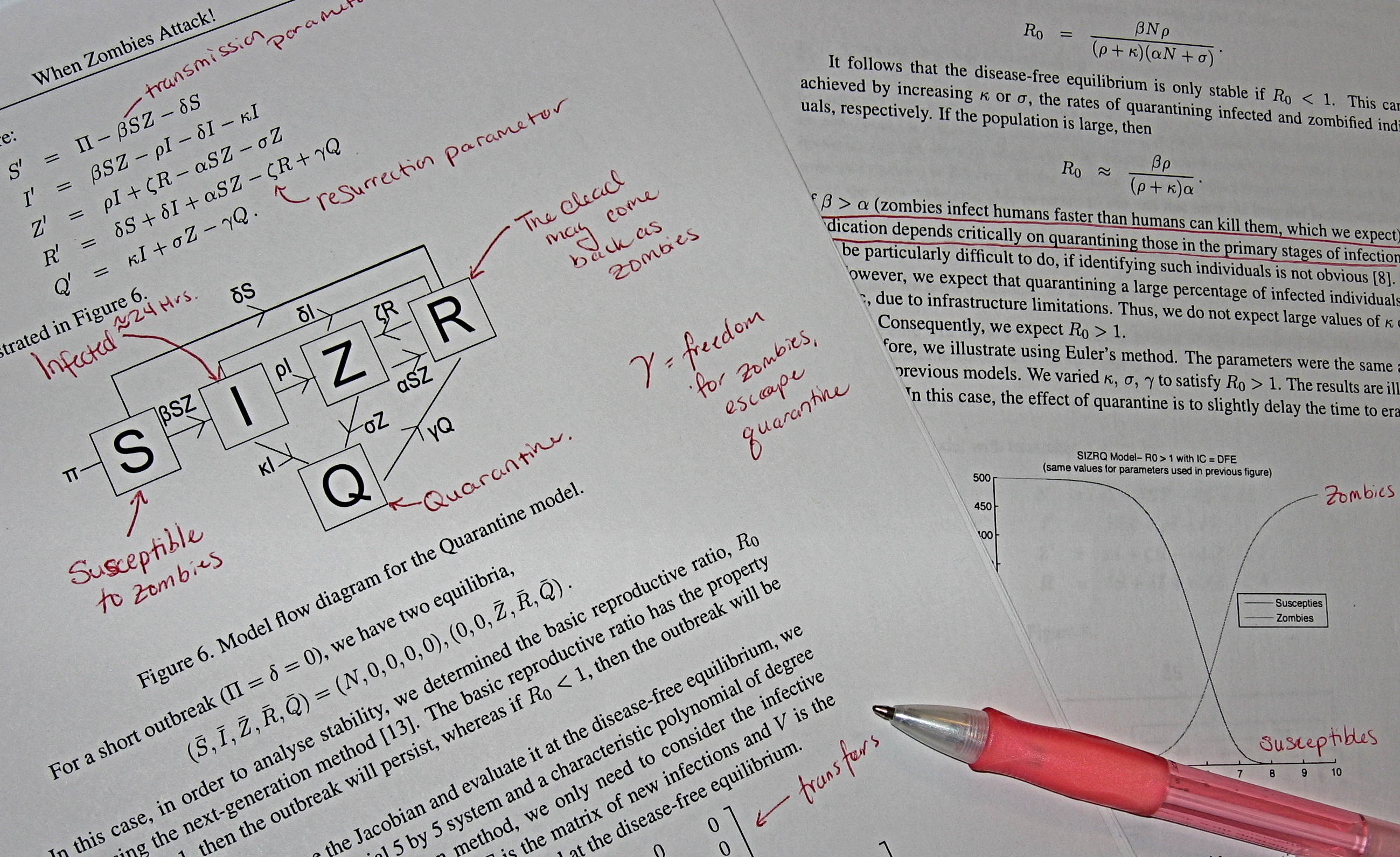

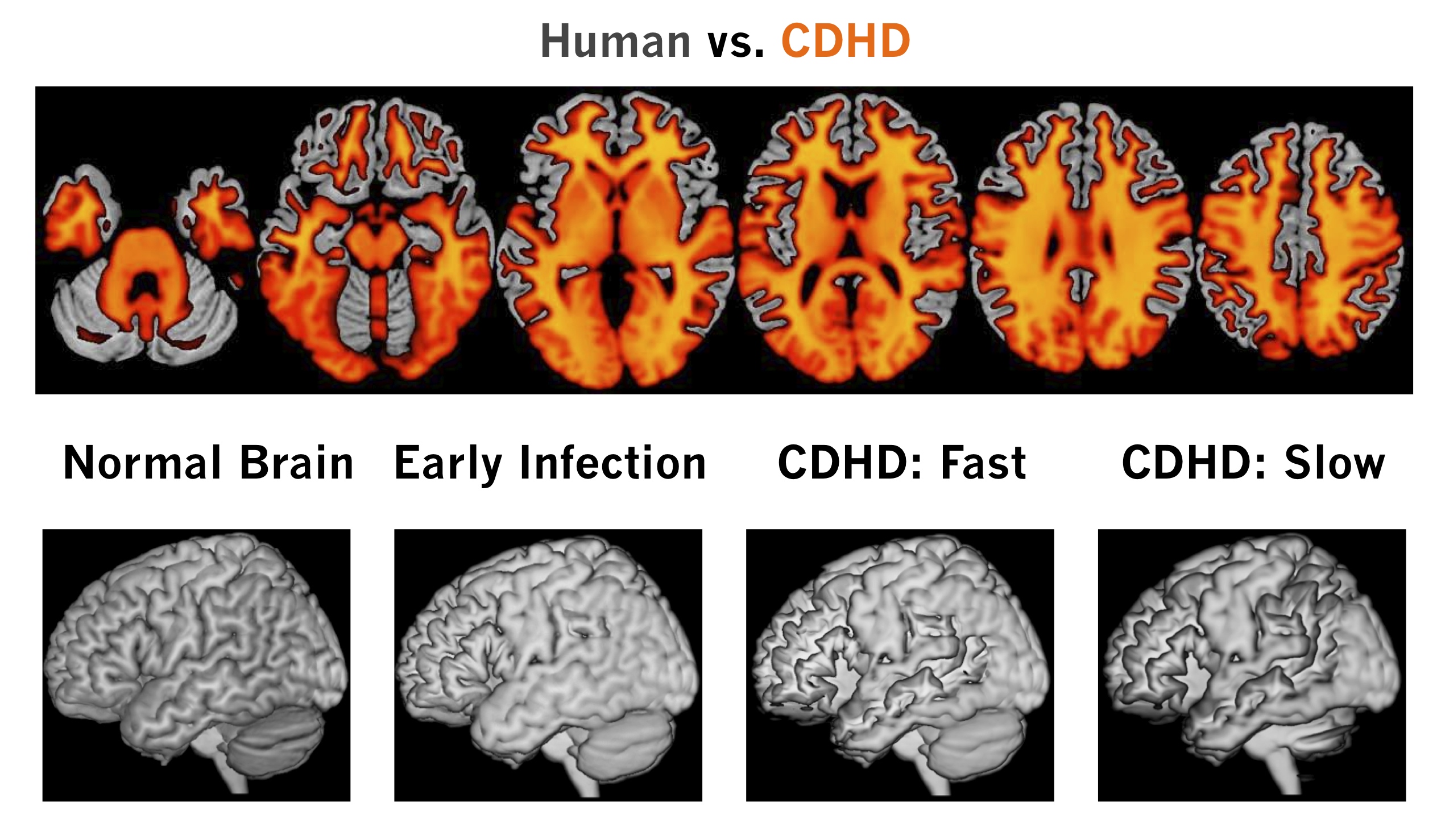

Using current understandings of the brain, advances in imaging, and a careful “examination” of zombie behavior, Voytek and his colleague, Dr. Timothy Verstynen at the University of Pittsburgh, diagnosed the undead with ‘Consciousness Deficit Hypoactivity Disorder’ and modeled how a zombie brain looks.

He defines CDHD by “ the loss of rational, voluntary, and conscious behavior replaced by delusional/impulsive aggression, stimulus-driven attention, and the inability to coordinate linguistic behavior.”

After Voytek presented their findings at this year’s Comic-Con and ZomBcon, I tracked him down to see if the undead are bringing life to scientific discussion (all the while denying my nerdy impulse to ask him what it’s like to sit next to Romero and his take on the heated question of fast zombies). It turns out zombies are spreading science.

At Comic-Con, Voytek sat on a panel with Max Brooks, author of The Zombie Survival Guide and World War Z, which is being made into a movie starring Brad Pitt.

“After our panel and during the Q&A session things got a little awkward; the majority of the questions weren’t directed at him, but rather were questions for me about the zombie brain. It was amazing,” Voytek says. “I had questions from students studying psychology and neuroscience, from a man who had suffered a stroke, a deaf gentleman, and so on. A group of us hung out and chatted about zombie movies and neuroscience for about 30 minutes after the panel.”

In his presentations, Voytek went through the seven classic symptoms of being undead and presented the neural explanation of each one. For example, the most obvious symptom, reactive-impulsive aggression—that unrelenting desire to devour the living—is likely caused by abnormalities in the orbital frontal cortex, the lower part of the frontal lobe. The orbital frontal cortex usually shuts down rage signals pumped out of by amygdala, a little almond shaped region in front of the orbital cortex.

In a case study of a man who had a steel rod go through his orbital frontal cortex, scientists found that without it you might switch from relaxing on the couch with some tea to savagely attacking someone in the garden.

“At its heart, the zombie genre is horrific. There are a lot of scary things in the world, and entertainment lets us encounter and confront our fears in a very safe way.”

Voytek and Verstynen developed explanations for the other six symptoms (loss of impulse control, motor deficits, language difficulties, attention problems, and memory loss), which Voytek chronicled this week in blogs. The final product is a comprehensive view of the zombie brain.

While the zombie brain has the public salivating, Voytek has gotten cheers from other scientists for his zombie breakthroughs. At zomBcon, members of the audience asked Voytek about the ‘herding’ behaviors of zombies in this season’s premier of The Walking Dead. A professor of wildlife ecology approached him afterward to say he enjoyed seeing the public engaged in a scientific discussion.

“It’s funny to me that the best method I’ve found to engage the public in science is with something so fantastical and made up! I think it’s similar to how pulp sci-fi novels from the 1950s and 60s got so many people interested in the space sciences in the 60s and 70s,” he says.

Whether it’s the horror, exploring the unknown, or the economy, the zombification of science is drawing people in.

“The wonder and imagination is what draws people to science,” Voytek says. “The joy of discovery is what keeps them there.

Zombies coming to a halloween near you: http://today.msnbc.msn.com/id/45087497/ns/health/#.Tq4_R94Uqso

They’re everywhere! Thanks for the link, Tanya!