For the past few months, my iPhone has been tracking my movements while I sleep. This isn’t because I’ve fallen victim to a National Security Agency sting (at least as far as I know). I have programmed my phone to keep close tabs on me – on purpose.

Of the many “a-ha!” moments I had in college, one was that I was a heavy sleep talker. Boyfriends and roommates regularly regaled me with tales of my nightly discourse, consisting of either short, Tourettes-like outbursts of gibberish phrases; or calm, seemingly lucid conversations on serious concerns.

One weeknight, after dreaming that my roommate and I were preparing to build a fort, I bolted upright and loudly asserted, “So Camille, how are we going to do this,” and then promptly fell back asleep. This is what my sleeping partners had to deal with.

As the stresses of full-time work and now graduate school have compounded, waking up has become onerous, even with a full eight hours of sleep. And it’s occurred to me that my sleep cycle may be screwy. Perhaps my morning malaise is linked to my nighttime babbles.

Within the past five years or so, many people have turned into self-monitoring fanatics as smartphones and cheap gadgets line our pocketbooks. We use our phones to track the number of steps we take in a day and how often strangers whistle at us on the street. Self data is the new fad.

I figured I’d hop on the bandwagon. I typed “sleep cycle” into my iPhone’s App Store search bar, and the Sleep Cycle Alarm Clock by Maciek Drejak Labs popped up. It claimed it would analyze my sleep and wake me in my lightest sleep stage, leading to a natural, easy return to consciousness. This will cure me, I thought.

I spoke to Patrick M. Fuller, assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School, about the soundness of this technology:

“The concept of taking information from your iPhone and applying it to sleep cycles is cute. The designers are well-intentioned and conceptually it’s neat, but the catch is that the utility of information derived from a phone tucked under your pillow is really limited.”

If you think you have a sleep issue, Fuller said, it’s doubtful that any form of data from your iPhone will be equivalent to a sleep study.

Fair enough. I put on my scientist hat and started feeding it data anyways.

Every night for three months, I’d tell it about my day: whether or not I exercised, if I was stressed, if I drank coffee or tea, if I ate late.

Then, I’d tell it what time to wake me up in the morning. If I needed to be up by say, 8 a.m., the app would begin to pay extra close attention to my movements starting at 7:30 a.m. The moment it would sense any wiggling or shifting within that 30-minute window, it would assume I was in a light sleep phase and the alarm would sound.

According to any introductory biology textbook, we’re supposed to oscillate between two main stages of sleep every night: NREM and REM.

NREM, or Non-Rapid Eye Movement phase, spans the time between wakefulness and sleep. Our eyes are still, our muscles occasionally twitch, and we sometimes jolt awake from a falling sensation. We don’t dream in this phase, and are easily awoken. The app classifies this stage as light sleep.

About 90 minutes after NREM, we enter REM, or Rapid Eye Movement phase, which normally occurs toward the end of the night. Our eyes move erratically and our brain activity heightens as we dream. Increased brain activity occurs simultaneously with muscle paralysis, which is why REM is also called paradoxical sleep. Kids who wake up with shaving cream and Sharpie doodles on their face at slumber parties usually were pranked in REM, because we’re not easily roused in this stage. The app classifies this phase as deep sleep.

When I placed my iPhone under my pillow each night, the phone’s internal accelerometer would sense how often and how intensely I moved. According to the app, any twitching or shifting meant I was in a light sleep phase. If I was completely immobile, I was in a deep sleep.

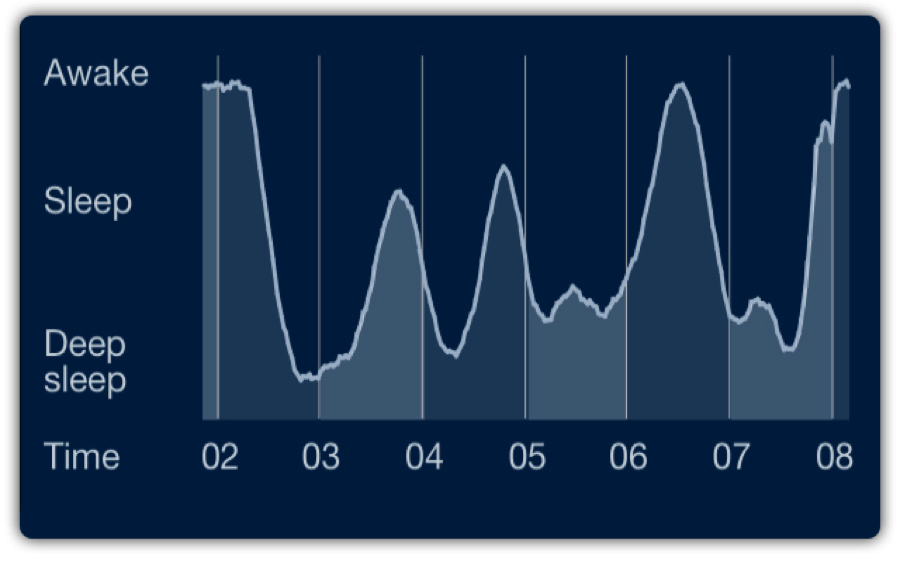

In the morning, the app would spit out a graph, called an actigraph, charting valleys and peaks corresponding to my movements over the course of the night. A normal graph is supposed to look like this:

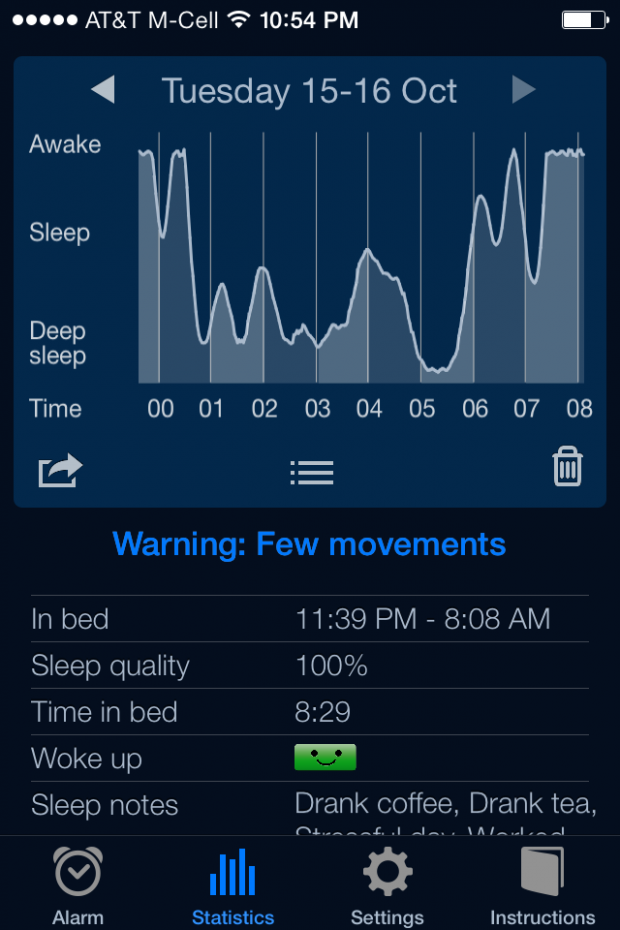

It would use this information to assign my overall Sleep Quality score, which is a percentage between 0 and 100. The app calculates Sleep Quality with some magical formula that incorporates data from the time I spent in bed and the amount of my movements over the course of the night. “In short, the more you sleep and the less you move, the higher Sleep Quality,” according to the Sleep Cycle website.

Sleep Cycle claims that regular alarm clocks are bad at waking us up because they sometimes happen to catch us in a state of deep sleep. But after using the app for a few months, I wasn’t finding a single pattern to my graphs. And more importantly, I wasn’t waking up refreshed.

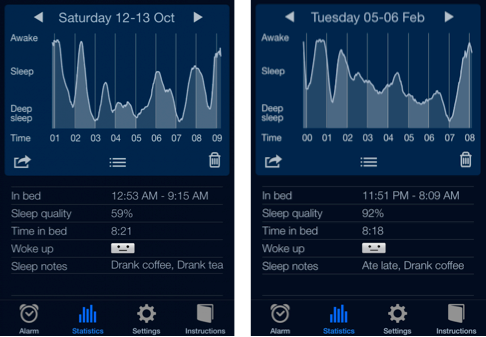

On rare occasions, I’d rise feeling rejuvenated after a solid 8 hours of sleep with healthy looking graphs, but only get 59 percent sleep quality. Other times I’d wake up feeling wrecked, with abnormal-looking graphs, but manage 92 percent sleep quality.

What gives? I contacted Sleep Cycle for input, but they didn’t get back to me.

I spoke to another expert, Aaron Morse, director of the Central Coast Sleep Disorder Center in Santa Cruz. He told me that while actigraphs have been used for years, they’re not very good at discriminating deep sleep from light sleep based on movements alone.

When we’re not moving, according to Morse, it doesn’t necessarily mean that we are in a state of deep sleep.

“REM is mistaken for deep sleep because our muscles are paralyzed,” said Morse, “but it’s not deep sleep. It’s neither deep nor light sleep. REM is actually physiologically very similar to the waking state and has a completely different purpose from resting,” said Morse.

He also explained that while REM does, in fact, occur more frequently in the morning, there’s isn’t any data showing that it’s harder to wake up from REM. In fact, waking up during REM is natural, according to Morse.

“I’m skeptical about whether these apps give any useful information at all. Bottom line, I don’t think these devices are very good at determining deep sleep from light sleep. And there is no data showing that waking up in light stage sleep is any better for you,” says Morse.

And I agree. While tinkering with Sleep Cycle’s neat graphs, charts and quality scores has made for an amusing wake up, it hasn’t improved my sleep in the slightest. And I still haven’t figured out why I am so tired in the morning.

But intelligent, portable devices like smart phones have allowed us to monitor ourselves in ways that only used to be possible with a high co-pay and an uncomfortable night’s rest in a sleep center. They bring an awareness to habits that may be affecting our well-being.

“Sleep is one of the pillars of good health, and we can’t operate efficiently at low sleep levels. If the app gets people to understand how they might improve their ‘sleep hygiene,’ I’m all for it. But one needs to be careful about interpreting the output they receive. The diagnostic utility of the app is pretty close to zero,” said Fuller, the sleep scientist from Harvard.

After speaking about the app’s limitations with experts, I’m probably going to retire it. But I’m happy to report that after months of aiming for the elusive 100 percent Sleep Quality score, I finally hit it last week. Whether or not this means I genuinely got the best sleep of my life is still yet to be determined. But now, at least, I can say that I went out with a bang.

What an unusual way to understand REM. I must say, I was taught that was the time you had dreams. Sounds like many are confused on what it is exactly. I enjoyed your page so much! Thanks for the info. I am still new to this and was using the blog to get comments on my writing only. I will try to blog better!

Thanks

Susan Wilson

Hi Susan, thanks your comment! You are right, REM is the time that we dream. But whether or not an iPhone can distinguish REM from other stages of sleep is debatable. Thanks for reading!